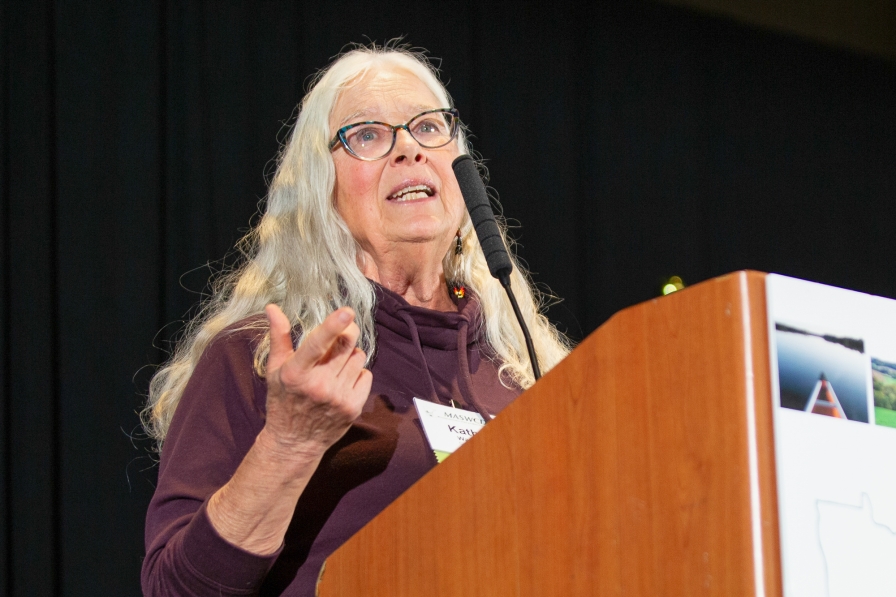

Kathy Wagner didn’t just take on a shoreline restoration project at her north-central Minnesota home, she took on a cause. That blend of personal action and public leadership earned her the 2025 Community Conservationist Award, presented by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) and Minnesota Association of Soil and Water Conservation Districts (MASWCD).

“Kathy’s work shows what’s possible when homeowners recognize their role as caretakers of the land,” said Glenn Skuta, Watershed Division director for the MPCA. “At the MPCA, we often look at water quality on a large scale — entire watersheds and statewide trends. Efforts like hers remind us how much difference one person can make.”

Known for having a hand in many corners of local environmental advocacy, she balances hands-on conservation work with service on community boards and an active presence in her Cass County lakes community.

Wagner’s most personal effort is shoreline restoration on Wabedo Lake, south of Longville, on property that once belonged to her parents’ resort, Wolf Lodge. The resort was the first on the lake, built in 1918, and Wagner’s family purchased the property in 1958. Wagner owns 230 feet of lakeshore and restored 150 feet of it.

For decades, people mowed to the water’s edge, which left the shoreline vulnerable to erosion. Frost heaves pushed up the lake’s sandy bottom, destabilizing the shoreline. County experts also suspect muskrats burrowed into the bank, worsening the problem.

She first considered investing in restoration in 2022, but the cost was daunting. An early estimate came in at around $40,000.

“I was a teacher, a single woman, and that was way beyond my budget,” she said.

As conditions deteriorated, the risk of collapse grew impossible to ignore. Invasive, nonnative grass covered the shoreline. Wagner had tried for years to remove it, planted native grasses, and stopped mowing, but erosion continued. At one point, a group of eight people, including engineers, inspected the site. When they all stepped onto the boat dock at once, a section of it immediately dropped. Clearly the project could no longer wait.

“Luckily, no one got wet, and it didn’t break anything,” Wagner said, laughing. “I thought it was funny that engineers didn’t think about weight load.”

Seeing the big picture

Wagner’s influence extends far beyond her own property. Dana Gutzmann, conservation manager for the Cass Soil and Water Conservation District (CSWCD), said Wagner has a rare ability to connect technical conservation work and community understanding.

“She explains complex environmental issues in ways that resonate with landowners,” Gutzmann said. “She helps people understand how individual choices affect entire lake systems.”

In nominating Wagner for the award, Gutzmann highlighted her consistency and follow-through. “She shows up, asks thoughtful questions, and volunteers her time to ensure projects succeed long after the initial planning stages.”

Wagner’s approach is shaped by her background as an educator. After returning to college as an adult, she spent 15 years teaching special education. Many of her students came from low-income households and relied on fish from public waters as food. “We don’t care about limits,” she recalled some of them saying. That reality prompted her to teach lessons about mercury in fish and why health guidelines matter.

“It’s about changing the language,” she said. “I always feel like we have to clean people’s glasses. Everyone sees things through their own lens. If we can change the words, we can change the thinking.” Instead of calling something like wild celery “weeds,” for example, she suggests “underwater plants.”

She retired in 2016 and cared for her partner until his death in 2019. With more time for conservation work, she became deeply involved.

“I’ve been gung-ho ever since,” she said. “The more I learn, the more I want to share. People are just not aware that salt on sidewalks or in their septic systems leach into the lake. Everything’s connected.”

Locals call Wagner “Mamma Wags,” a nickname that reflects her visible and familiar presence in the community. Over the years, Wagner has been involved with numerous organizations, including the Wabedo-Little Boy-Cooper-Rice Association, the Association of Cass County Lakes, the We Are Water exhibit, county advisory committees, watershed restoration planning, and MPCA water quality monitoring. She helped establish 75 boat-cleaning stations to prevent the spread of invasive species. She even grows 2 acres of pick-your-own blueberries.

“I forgot about all these things that I’ve been doing,” Wagner said. “It has always been about protecting the lakes.”

Crucial work completed

The shoreline project ultimately cost far less than the original estimate. Still, at $19,000, it was no small expense. Because the work benefits the watershed, CSWCD was able to reimburse Wagner for half the project using watershed-based Implementation funds from the Clean Water Fund established by the Clean Water Land and Legacy Amendment.

The results quickly became visible. A native seed mix produced new species throughout the growing season. Early spring brought spiderwort, anise hyssop, joe pye weed, Bush’s poppy mallow, butterflyweed, lanceleaf coreopsis, coneflowers, wild bergamot, blazing stars, goldenrod, blue vervain, and asters. Sedges, bluestems, and shrubs such as red dogwood, highbush cranberry, chokecherry, and willow added structure and stability.

“Flowers kept appearing as the summer evolved,” she said. “The many colors that show up are amazing. Even the grasses had different textures.”

The restoration crew installed coir logs (long coils staked to the ground) and jute blanket, a biodegradable netting. They also shaped a small valley to slow runoff and left one area planted with native grasses to allow kayak and canoe access. Wagner also paid to replace her septic system, a $15,000 investment she considers essential.

Early success depended on regular maintenance. Wagner watered daily in 2023 and 2024. The new flowers attracted bees and other pollinators.

“You could just stand there and hear them buzzing all around,” Wagner said.

Rethinking ‘pristine’

Wagner works closely with the CSWCD and encourages landowners to seek help if needed and recognize how everyday actions affect water quality. She encourages landowners to take on what they can, whether through programs such as Lawns to Legumes or simpler steps.

“Don’t cut the lawn; let things go natural; plant some trees,” she said.

Gutzmann said that Wagner’s commitment is rooted not in recognition, but in responsibility, a belief that lake stewardship is a shared responsibility.

“Kathy understands that protecting our lakes means meeting people where they are, and helping them see that conservation isn’t about restriction, but about care,” she said.

Wagner said she hopes others will rethink the idea of a so-called “pristine” shoreline.

“We want wild,” she said. “Wild is best. Let there be wild!”