MPCA’s chloride reduction grants cut salt use to the benefit of the river and Marshall residents’ pockets

A decade ago, Scott Przybilla probably thought as much about water softeners as he thought about his sock drawer. Both occasionally needed to be restocked, both served a function, and that’s about it. Out of sight, out of mind.

But as the assistant superintendent for the wastewater treatment facility in Marshall, concerned primarily with the cleanliness of the water that leaves that plant and enters the Redwood River, he also had to consider the amount of chlorides passing through the facility, especially after the MPCA required the facility to drastically cut that amount in 2014.

Those chlorides came from salt, and the salt overwhelmingly came from Marshall residents’ water softeners. Przybilla suddenly had to think a lot more about water softeners.

“I know more about water softeners now than I ever think I’d need or want to know,” he said.

He had help in that quest: An MPCA chloride reduction grant that reduced salt use in the city up to 90% by upgrading water softeners, one of a series of grants for cities in the state struggling with reducing chloride.

Where the chloride comes from

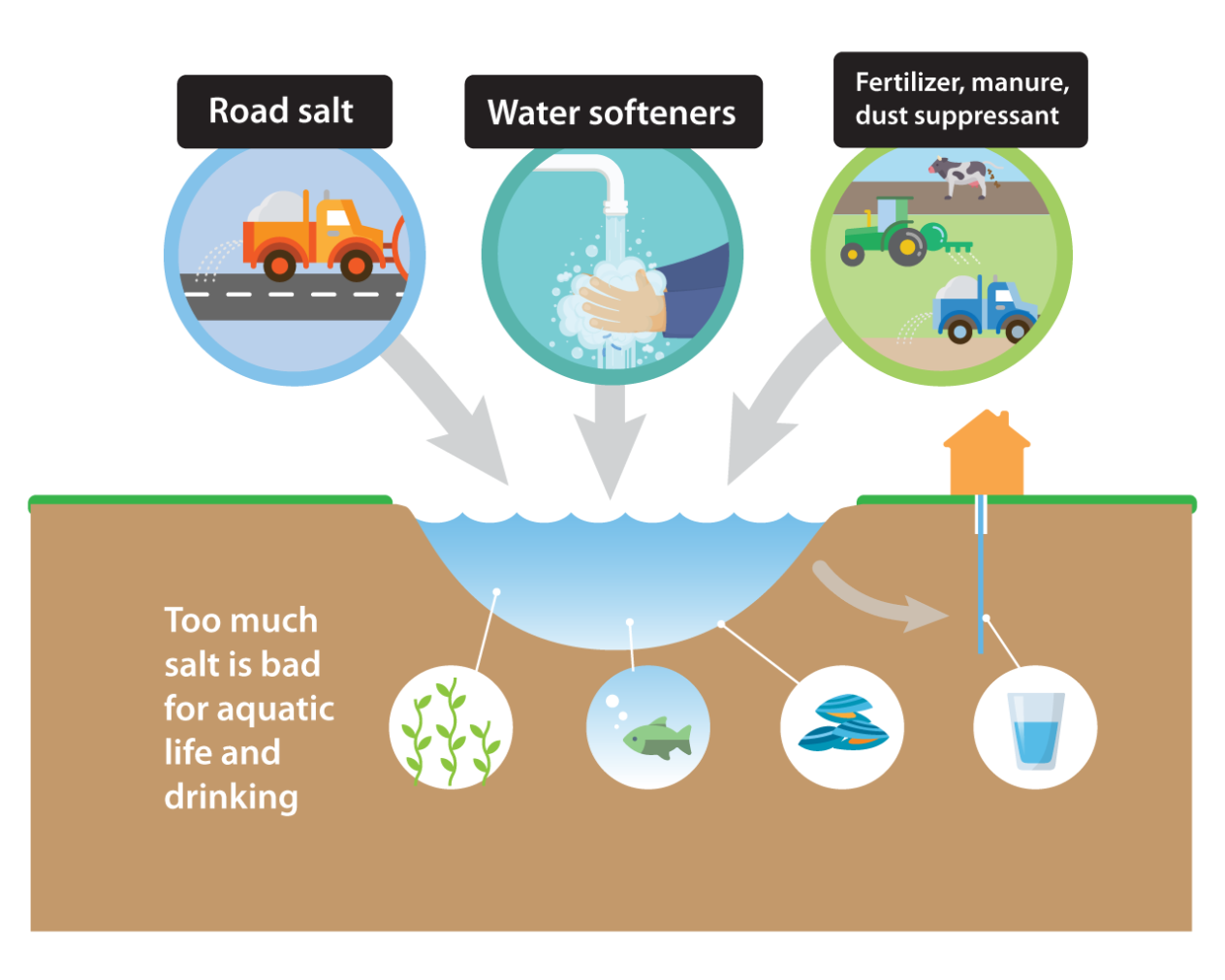

To many, if not most people in Minnesota, it’s easy to see how the salt used for de-icing roads, parking lots, and sidewalks during the winter can lead to chloride pollution. Towering piles of salt — primarily sodium chloride — are a common sight across the state ahead of every winter. Then, after the salt has done its job, it flows into storm sewer systems or into roadside ditches and on into lakes, rivers, and streams where it proves toxic to wildlife and vegetation and poses a threat to groundwater and aquifers that supply drinking water.

So most chloride pollution must come from salt used for de-icing, right? Not necessarily, according to Brooke Asleson, who coordinates the MPCA’s chloride reduction program.

Chlorides can come from multiple sources, including dust suppressants, fertilizers, industrial processes, and water softeners. Chloride doesn’t break down or degrade, so over time it turns fresh water saltier. As a result, 68 lakes and streams are now on the state’s impaired waters list for exceeding the state’s standard for chloride pollution.

“At this point, most facilities are just starting to figure out where their chloride is coming from,” Asleson said. “Water softeners are likely the primary source of chlorides for most wastewater treatment facilities in Minnesota.”

Considering groundwater is inherently hard — while in the ground, it constantly picks up the minerals it’s in contact with — and 75% of Minnesotans rely on groundwater as their primary source of water, it’s little surprise most Minnesotans have a water softener tucked away in their basements and utility rooms.

As Przybilla noted, while the Redwood River runs right through the middle of Marshall — under bridges, past parking lots, and right through the heavily traveled downtown — it’s not listed as impaired for chlorides until after the wastewater treatment facility on the downstream side of the city.

“Basically, road salt use is not an issue in Marshall,” he said. “The chloride is all going into the river from the wastewater treatment plant.”

Hard water leads to more chlorides

Historically, Marshall has had to contend with hard water — up to 50 grains per gallon, which the Minnesota Water Quality Association considers very hard. So water softeners were an accepted part of life for the city’s residents and businesses.

“Everybody had a water softener, usually a big water softener,” Przybilla said.

Like Przybilla, most people and businesses in the city didn’t think much about those water softeners as long as the water coming out of the tap allowed soap to lather up to their liking.

“Water softness is a very personal choice,” Asleson said.

The City had taken steps to address the water hardness and deliver softer water to residents in 1999, when it installed a lime softening system for the municipal water supply, then again in 2019, when it expanded its water treatment plant to add soda ash to the lime softening.

Both of those projects managed to get the hardness of the water going into houses and businesses down to eight grains per gallon. Chloride levels did come down too, Przybilla said, but not nearly as much, even with an initial round of outreach aimed at getting residents and businesses to adjust the settings on their water softeners.

“With the water softener expansion and outreach, we went from around 500 to 700 milligrams per liter of chloride in our wastewater discharge down to around 400,” Przybilla said. Not bad, but also nowhere near the 261 milligrams per liter that the MPCA said the plant had to reach in 2014.

Further reducing the hardness of Marshall’s water was out of the question. The expansion of the water treatment plant already cost $11.6 million. A reverse osmosis system to treat the wastewater for chlorides would have cost even more money. But getting Marshall’s residents and businesses to put less salt in their water softeners would be a far more cost-effective approach. That’s where the MPCA’s chloride reduction grant came in to help.

Cost (and salt) savings from rebate program

The 2022 grant enabled two southwest Minnesota cities — Marshall and Worthington — to fund programs aimed at either replacing or optimizing water softeners.

Traditional ion-exchange water softeners provide soft water by passing hard water through tiny resin beads that pick up the minerals that make the water hard. The salt that homeowners pour into their water softeners forms a brine solution that flushes the minerals out of the resin beads. Soft water goes to the house’s plumbing while the minerals and the brine solution go down the drain.

Older models typically ran on a timer, flushing the resin beads regardless of whether they needed to be flushed, thus wasting salt. Newer, demand-based ones typically run depending on how much water has passed through them, which can use salt more efficiently.

But most people just leave their water softeners on the factory settings, which aren’t necessarily in tune with the hardness of the water entering the water softener and can still use far more salt than necessary, according to Carolyn Dindorf, who worked with Marshall and Worthington to administer the rebates for consultant Bolton & Menk.

“Lowering the hardness of the water coming in will only do so much,” she said. “The water softeners must be removed, adjusted, or replaced to reduce salt use.”

While homeowners and business owners aren’t expected to be able to optimize their water softeners, Dindorf said that many plumbers and other water softener installers didn’t have the training necessary to do so either.

To convince residents and business owners to upgrade or optimize their water softener, Bolton & Menk worked with Marshall and Worthington officials to create a handful of incentives, including $500 to $700 rebates for replacing timer-based water softeners, $50 payments to contractors for every water softener optimization, and $500 payments for residents who got rid of their water softeners altogether.

In Marshall, nearly 300 homeowners and businesses took part in the program, reducing salt use by up to 320,000 pounds per year. For individual homeowners, salt reduction ran as high as 86%; as Przybilla noted, that meant a typical household was able to reduce its salt use from four bags of salt per month to two bags a year.

“That’s a lot of cost savings, plus you don’t have to carry salt down to the basement anymore,” he said.

A similar rebate program that Bolton & Menk created with the MPCA chloride reduction grant funds for Worthington residents and businesses led to more than 200 replacement and retrofitted water softeners, reducing salt use by as much as 212,000 pounds per year.

More work left to do

While the rebate program did reduce the Marshall wastewater treatment plant’s chloride numbers down to about 300 milligrams per liter, according to Przybilla, the City still has work ahead of it to get that number below the MPCA’s 261 milligrams per liter chloride limit.

“Our main focus is still replacing and optimizing residential water softeners, so the City decided to continue the rebate program using the wastewater budget,” Przybilla said. “But we’re also working on the industrial side to get all our businesses on compliance schedules to drop their chloride amounts.”

Earlier this year, the MPCA issued a chloride variance for Marshall, giving it until 2034 to meet its chloride limit. Worthington is also operating under an MPCA variance and has until 2036 to meet its chloride limit.

Przybilla sounded confident the City can do so: Five or six people a month take advantage of the continued water softener rebate program in Marshall.

“Most people who hear about it are more than happy to adjust or replace their water softeners,” he said.

Bolton & Menk and the MPCA’s chloride reduction program also learned how to fine-tune its approach to such rebate programs, Dindorf said, which will help any cities that take advantage of further grant rounds.

Rebate programs alone won’t get cities to meet their chloride limits, she said, “but rebates do help them move in that direction.”

The lack of training in water softener optimization that Bolton and Menk discovered when creating the rebate program has also led the MPCA’s chloride reduction program to create a training for plumbers and other water softener installers. The new certification training for water softening will launch this fall.