MPCA’s Smart Salting program aims to cut chloride pollution from excess road salt use while keeping roads safe in winter

Even in summer, the effects of road salt use are easy to spot. Rusted fenders on cars and trucks, corroded bridges and infrastructure, and brown strips of grass along the edges of highways all serve as reminders of the tough winters that Minnesotans endure.

Less visible are the effects of salting on Minnesota’s waters, which in recent decades have experienced steep increases in concentrations of the salts used for de-icing roads, parking lots, and sidewalks. More salt in surface waters can not only harm wildlife and vegetation but also pose a threat to groundwater and aquifers that supply drinking water.

What’s worse, salt is just too good at what it does for what it costs, leading Minnesotans to rely heavily on it to keep roadways, parking lots, and sidewalks free of ice. So limiting the amount of damage salt does to the environment means limiting how much salt road crews, private contractors, and homeowners apply every winter without compromising safety. That’s where the MPCA’s Smart Salting program steps in.

“There’s a lot of science, a lot of thought that goes into managing snow and ice,” says Brooke Asleson, who coordinates the MPCA’s chloride reduction program. “With Smart Salting, we’re breaking down the science behind deicers and helping winter maintenance professionals determine the best tool for the job to keep surfaces safe and protect the environment.”

The problem with salt

Salt works to de-ice roads by making it difficult for water to freeze. Sodium chloride, the cheapest salt available, starts to lose effectiveness at about 15 degrees Fahrenheit. Other salts like calcium chloride and magnesium chloride work more effectively at lower temperatures but cost more and prove even more damaging to vehicles and infrastructure.

According to one study, the Twin Cities metro area uses 250,000 tons of salt on its roads each year, while the entire state of Minnesota uses more than 400,000 tons, or about enough salt to fill a line of single-axle plow trucks stretching end-to-end from Minneapolis to Duluth and back.

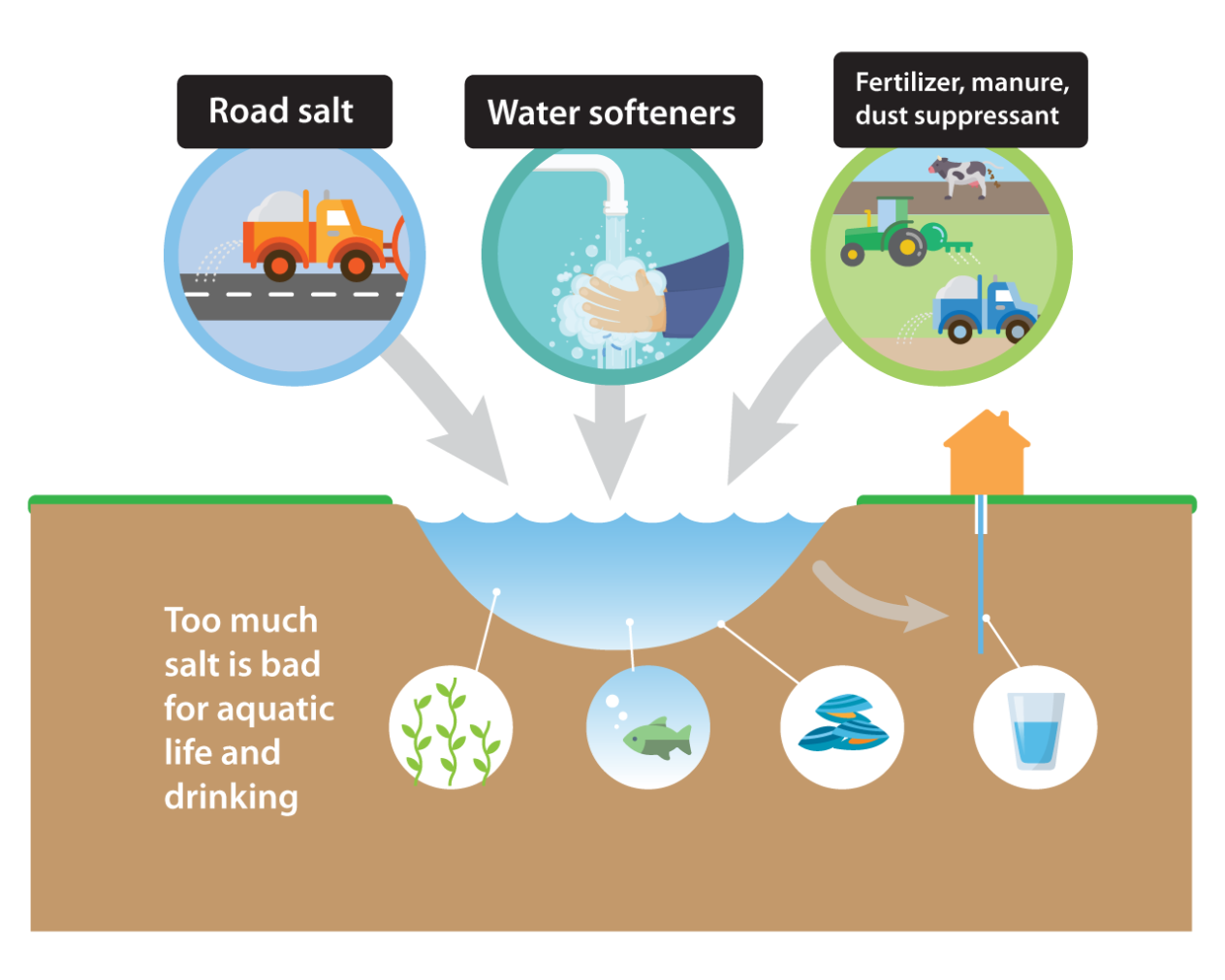

Salt used for de-icing is the largest source of chloride pollution in the state, but it’s not the only source. Other significant contributors include fertilizer, water softening systems, and even dust control products for gravel roads.

Whether via runoff, stormwater systems, or wastewater systems, all that chloride makes its way into lakes, streams, rivers, and groundwater, where it hangs around. Chloride doesn’t break down or degrade, so over time it turns freshwater saltier, making the water toxic for native fish, bugs, and amphibians. As a result, 54 bodies of water are now on the state’s impaired waters list for exceeding the state’s standard for chloride pollution, with 13 more proposed for the 2024 list. Only two bodies of water considered impaired for chlorides — Bevens Creek and the south fork of Crow River, both in Carver County — have ever been removed from the list.

According to Asleson, some research has gone into less problematic chemicals and materials than chlorides, “but there’s no alternative that’s good for the environment and that’s effective.” Acetates, for instance, break down after 24 to 48 hours, but also deplete oxygen from the water while they do so, which may cause fish kills. And while sand is often used to help provide traction, it doesn’t melt ice and it too can harm ecosystems if it gets flushed into waterways.

“There’s no silver bullet,” Asleson says. “This depends on all of us working together— everybody using salt, from homeowners to MnDOT, which is leading research on technologies to minimize salt use and alternative products.”

Learning from experts

To counter the harmful effects of chloride, the MPCA created the Smart Salting program, which offers training and certifications primarily to snowplow drivers and private contractors to provide them with support and resources to use less salt on roads and other surfaces in the winter.

“We do not recommend any practices that compromise public safety — that's our number one priority,” Asleson says.

Instead, the recommendations that come out of the program focus on strategic and judicious use of salt and on practices that can, in some cases, improve safety.

“If you use the wrong product in the wrong situation, it can actually create unsafe conditions,” Asleson says. “We know, for instance, that magnesium and calcium chlorides are hygroscopic — they pull moisture out of the air and to themselves— so if you apply them when there’s any kind of humidity in the air, dry pavement can become wet and icy if temperatures drop.”

In addition to trainings for municipal snowplow drivers, the Smart Salting program offers trainings for property managers and for community leaders and local elected officials.

The trainings, Asleson says, are based not just on the latest research from industry experts but also on the experiences of snowplow operators and property managers. Many co-instructors for the trainings, in fact, are winter maintenance professionals.

“It helps give it a little more credibility,” she says. “The unique part of our training program is that we’re not telling people what to do — it’s a real ground-up approach in which we’re learning from the participants and the host sites, who are all passionate about the environment.”

She points to Plymouth on the metro area’s west side as a good example of a city that has successfully implemented Smart Salting practices and that has offered to share what its road crews have learned with other municipalities.

Putting training into practice

Not far from the massive salt shed that the city fills with mounds of white salt every fall, Plymouth has a cavernous garage at its city maintenance facility that houses its fleet of 18 plow trucks, and it’s in that garage where much of the city’s salting innovation has taken place.

That innovation can be as simple as a metal plate welded to the back end of the trucks to keep the salt from dropping straight into the spreader. “We try not to be the trucks that you see sitting at a light spinning and dropping a mound of salt,” says Torrey Keith, Plymouth’s street supervisor.

That innovation can also come in better ways to mix and spread salt brine, which is preferable to granular salt because the brine won’t scatter and bounce off roads.

“We’ve been using liquids since the 1990s and making improvements every year since,” Keith says. “We were one of the first to put a brine tank in the box of a plow truck — we called it the octopus because of all the hoses coming out of it.”

In the cab of one plow truck, Keith demonstrates how modern spreading equipment mounted to the trucks can adjust slurry mixes and application rates on the fly. While the driver has control over those settings, the trucks are also networked, so Keith can monitor the data that the trucks collect and report, then radio to the drivers to adjust their settings if application rates are too high.

Other big contributors to Plymouth’s salt savings are the city’s policy decisions, based on Smart Salting best practices. “We don’t have a blanket bare pavement policy, for instance,” says Ben Scharenbroich, the city’s water resources supervisor. “We’ll aim for bare pavement for the main roads, hills, and bridges, but for everything else, we’ll just scrape.”

The drivers are all on board, too. Plymouth has mandated Smart Salting training for its 27 snowplow drivers and for any other city employee who can get behind the wheel of a plow in an all-hands-on-deck situation.

“Historically, this has been supported from the top down,” Scharenbroich says. “If we’re doing things that make the city a better place to live and are the right thing to do, it’s more likely that city leadership will support our work.”

Reducing salt, cutting costs

While salt usage naturally varies with the severity of winters from year to year, Plymouth has seen a marked decrease in how much total salt it uses, from as much as 3,200 tons per season 10 years ago to an average of less than 1,900 tons per season over the last nine years. The city also uses about two-thirds less salt per snowstorm than it did a decade ago.

Not only does that help keep salt out of area waters — nearby Parkers Lake is one of those bodies of water on the impaired waters list for chlorides — it also represents a cost savings for the city. Last year, Plymouth was able to spend $38,000 less on salt than what it had budgeted even though the city recorded more snowstorms and more snow overall than any year in recent history.

That cost savings extends beyond buying less salt, too. Keith says the city now spends half the time it used to cleaning salt off the streets in the spring. And as Asleson notes, every ton of salt saved means another $3,000 not spent on related expenses: everything from replacing dead grass to filling potholes to recarpeting building entrances.

“It’s the only time you can save money when reducing a pollutant,” Asleson says.

While Asleson says that she and the hosts of the Smart Salting trainings keep an eye on research into chloride alternatives, the trainings are having an overall positive effect. The program trained more than 1,100 people last year alone, and research shows that every municipality that implements the salt-reduction practices and strategies in the trainings can cut its salt use by 30 to 70 percent.

“We know how complicated and difficult it is to balance public safety and cutting salt use,” she says. “But we also believe we can have it both ways — we can make the waters cleaner and still have safe roads.”