Willernie-based company takes MPCA’s $10,000 Green and Sustainable Chemistry Prize

Cody Bates found he has to be careful when discussing the manufactured glass beads that the company he co-founded, Revitri, has developed.

“I can sound like I’m rolling into town in the 1840s with a magical cure-all elixir,” he said.

But the benefits that could result from widespread use of the Revitri beads — including lighter parts for electric cars, less energy-intensive manufacturing processes, less material going into landfills, and more energy-efficient homes — convinced judges from the MPCA to award Revitri with the agency’s $10,000 Green and Sustainable Chemistry Prize at the 2024 MN Cup innovation awards.

Improving the glass bead

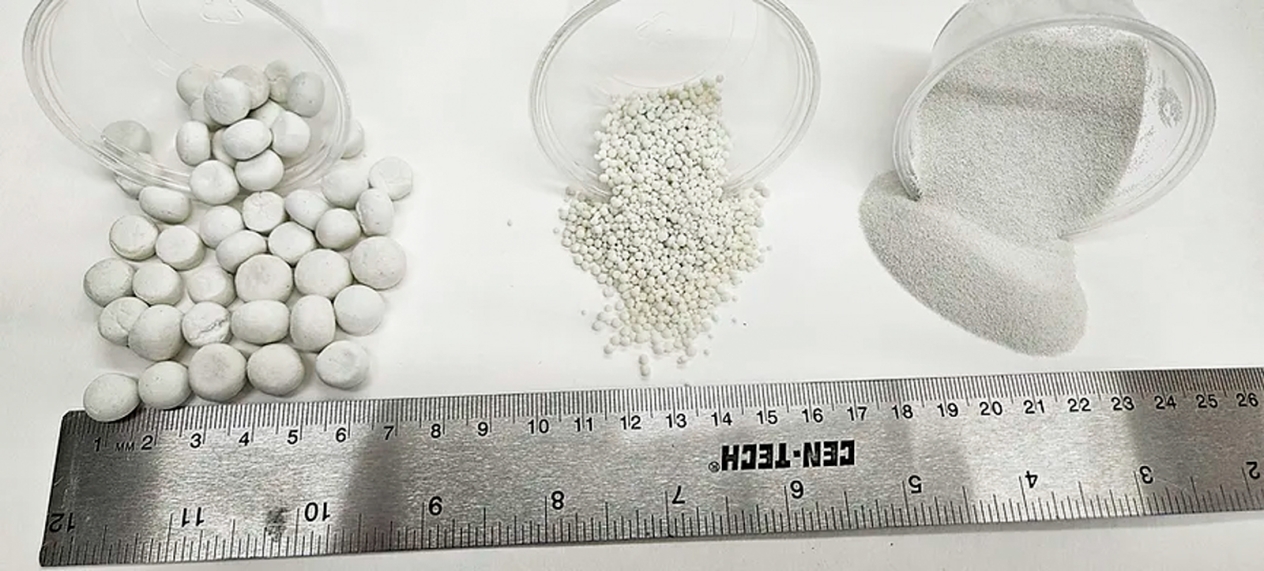

Bates and his co-founder, Ken Klann, describe the beads’ structure as something like a malted milk ball with a foamy, airy center and a hard outer shell. That structure makes the beads stronger and lighter than the hollow glass beads traditionally used as filler in products like automotive plastics. Meanwhile, the closed-cell nature of the internal foam structure makes the beads great thermal insulators.

The idea isn’t necessarily new, Klann said, but the breakthrough came when he was able to figure out how to create the beads in his garage in Willernie at far lower temperatures than had previously been used.

He was able to do so, he said, by carefully selecting chemical additives that control how much the interior of the beads puffs up during production.

Rather than use ovens that require massive amounts of natural gas or electricity to get up to thousands of degrees, Klann said the process to create Revitri’s beads could use simple concentrated solar — essentially a big magnifying glass — to generate enough heat to puff up the beads, reducing both the cost and carbon footprint of production.

“The cost of production for glass beads comes primarily from energy consumption,” he said. “We lowered that by 75%, which is a huge step.”

The beads themselves also improve upon traditional glass bead properties. They’re as much as 40 times stronger and as much as nine times less dense — light enough to make concrete float. While Klann can make them about the size of an actual malted milk ball, he can also make them much smaller, about the scale of beach sand.

Putting the beads to work

Bates and Klann, who were already frequent collaborators on other projects, decided to develop the glass beads about six years ago after a conversation about insulating Klann’s basement. Klann figured some sort of additive in concrete blocks like a glass bead could help make basement walls warmer, so he got to work.

Klann’s idea of making better basement walls has since expanded to creating entire houses out of lightweight concrete filled with the beads.

“We could replace lumber, drywall, insulation, siding, all of that, with fully concrete wall panels to build a more energy-efficient house cheaper than we do today,” he said. “This would even be an ideal aggregate for the cement they’re using to 3D print houses now.”

Meanwhile, Bates — whose background is in sales to the plastics industry — has started to pitch Revitri’s glass beads as a better filler for the nylon plastics used in car parts.

“Auto manufacturers are doing everything they can to make their cars lighter to meet fuel-efficiency standards and to increase range of electric vehicles,” he said. “These beads can offer the same properties as the beads they’re using now, but because they’re less dense, the parts will weigh less. And because they’re less dense, they’ll require less energy to heat and cool in the production process, which means lower production costs and quicker turnaround time.”

Peder Sandhei, who presented the Green and Sustainable Chemistry Prize to Revitri at this year’s MN Cup, agreed that the beads will have many environmental benefits.

“The judging team was impressed with the unique chemistry developed that allows bonding to both glass surfaces and polymers that facilitate the ability of the beads to bond with plastic,” Sandhei said.

Waste material as feedstock

The beads’ environmental benefits even extend to the raw material for the beads: tiny bits of crushed glass that would normally go to the landfill.

“During recycling, glass is sorted for color and size, but most of it gets broken down too small to sort so there’s no customer,” Klann said.

While Revitri’s beads could be made from high-quality recycled glass, the feedstock has to be ground to a very fine powder for production anyway. It makes sense then to use the low-quality glass, and Klann has already developed a process to clean that glass before pulverizing it.

“We’re getting results as good as if we were using new glass,” Klann said.

The low-quality glass not only costs next to nothing, but it will also allow Revitri’s eventual customers to advertise that their products use post-consumer recycled content.

Production in the Twin Cities

To date, Revitri has operated on a bootstrap budget with Klann as its only employee. Bates said the Green and Sustainable Chemistry prize from the MPCA comes at a good time: Bates and Klann just received their patent for the process in late September and are now planning a pilot production plant in the Twin Cities metro area. They’ve already arranged to take up to 14 million pounds of crushed glass per year from a Minneapolis recycler.

Both Bates and Klann said they see applications for the beads beyond lighter cars and warmer houses.

“We have a whole file of ideas to pursue, but we’re actively ignoring all other applications to focus on getting the beads into production,” Klann said.

Bates said nothing like these beads has come around in the plastics industry since carbon fiber in the 1960s.

“We’re excited about this opportunity,” he said. “To us, it’s such a neat product because it puts less carbon in the air, it increases recycling, and it keeps stuff out of the landfill. It has such an overall positive environmental impact, we can’t help but feel if we’re getting away with something.”