A lot of chloride pollution in Minnesota comes from inefficient water softeners. Here’s how to cut your salt use.

As with salt in our meals, a moderate amount of salt in a water softener isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For many Minnesotans who live with hard water, that salt works to lather their soap and stop the buildup of scale in their appliances.

Also as with salt in our meals, too much salt in a water softener is harmful. It drains wallets, strains backs, and is toxic for the environment. And it’s often not necessary to use much salt in a water softener.

“People don’t often pay attention to the settings on their water softeners,” said Brooke Asleson, who coordinates the MPCA’s chloride reduction program. “Most of the time, they’re still on the factory setting with the highest chloride discharge.”

So how can you tell how much salt is too much and, more importantly, how can you cut the salt that goes in your water softener and still enjoy its benefits?

What’s the problem with too much salt?

The salt that goes into water softeners is a chloride, and chlorides don’t break down in the environment, so over time they turn freshwater saltier, making water toxic for native fish, bugs, and amphibians. As a result, 68 lakes and streams now exceed the state’s water quality standard for chloride pollution. Chloride can even move into groundwater, risking local drinking water supplies.

Chloride pollution can cost city residents too. Even though municipal wastewater treatment plants can’t remove the chloride or salt in wastewater, most of which comes from water softeners, they’re responsible for reducing chloride in their discharge to the state’s rivers, lakes, and streams. That means they have to reduce or eliminate sources of chlorides entering wastewater, which can be costly and can lead cities to increase water and sewer rates.

Why do I need a water softener in the first place?

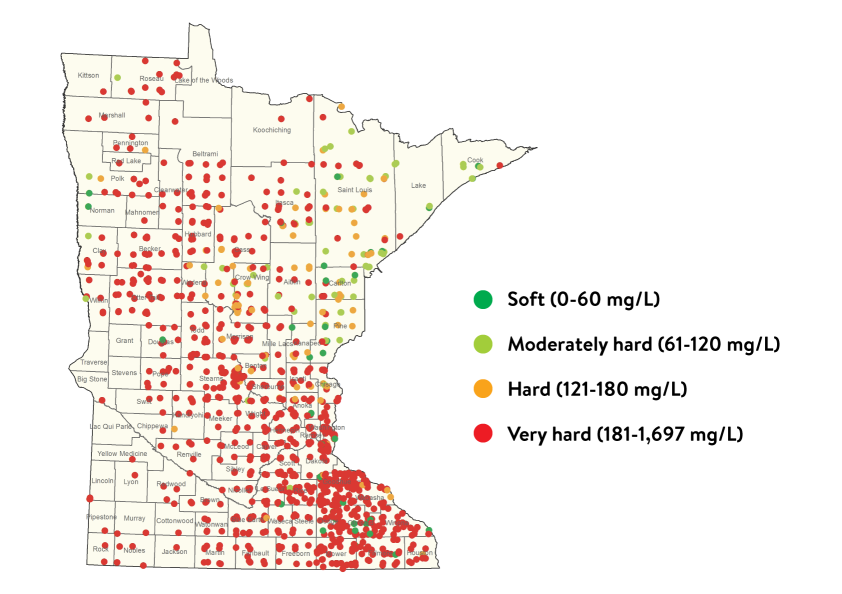

Water becomes hard by coming into contact with minerals underground, so private well owners and anybody who gets city water sourced from groundwater — about 75 percent of Minnesotans — has to contend with hard water.

Those minerals — usually calcium and magnesium — contribute to soap scum, poor soap lathering in the shower, and scale in a house’s pipes.

A water softener works by trapping those minerals in tiny resin beads, then periodically flushing out the resin beads with the brine solution created by pouring salt into the softener. Soft water goes to your tap while the minerals and the brine solution go down the drain.

But, depending on the hardness of the water coming into your house and the age of your water softener, you may be using far more salt than you need to get soft water.

How do I cut back my salt use?

First, determine if you really need a water softener. Hard water causes no harm — except to appliances like water heaters and dishwashers — so you may not mind it.

“Water softness is a very personal choice,” Asleson said.

In addition, your city may already be treating your drinking water for hardness; if that’s the case, your house’s water softener may be redundant.

For those who have a water softener, you can still cut back your salt use. Limit the number of faucets using softened water to reduce demand on the water softener. Your outdoor spigots and sprinkler system can make do with hard water.

You may have an older timer-based water softener chugging along in your basement; these run at set intervals, regardless of whether the resin beads need to be flushed. To keep from wasting all that salt, you can replace your timer-based water softener with a more efficient demand-based water softener.

Demand-based water softeners run after you’ve used a certain amount of water and use only as much salt as you need. Water softener installers can fine-tune them to the hardness of the water coming into your house.

“Water softeners are kind of like furnaces, in that you need to have a professional come in to take a look at the settings every couple of years,” Asleson said. “Every device is different and has its own little process.”

Another option, a water conditioner, offers some of the same benefits as a water softener such as reducing scale without the need for salt. Water conditioners are more expensive, Asleson said, and the feel of the water differs from soft water because water conditioners do not remove minerals from hard water, so they may not be for everybody.

Some companies even offer water softener tank exchanges, in which they swap a tank of soft water for a depleted tank, then recharge the latter at their own facility. You still get all the advantages of soft water without adding to your city’s chloride load.

Does cutting salt from my water softener work?

It’s not often that doing something good for the environment saves money, but as Asleson noted, most chloride reduction efforts do just that.

One recent study in Marshall found that residents who replaced or optimized their water softeners reduced the amount of salt they used every year — and thus the amount of chlorides that they sent into the nearby river — by 86 percent. That’s roughly equivalent to going from four bags of salt a month to two bags per year.

Multiply that by the going rate for a bag of salt, and you can see how the savings quickly add up. Some cities in Minnesota even have rebate programs for residents who upgrade to high-efficiency water softeners, potentially putting even more money back in your pocket.

Maybe use that money you’ve saved for a nice meal out. Just tell the waiter to go easy on the salt.