Climate change helps fuel extreme Canadian wildfires behind majority of alerts

The records that fell in dramatic fashion across the state this summer weren’t the type to generate much celebration. Instead, they kept Minnesotans indoors and their moods sedate as one air quality alert after another — more than in any previous year — swept over the state.

The alerts aren’t over yet, either, with more hazy, smoke-filled days likely on the way.

“The Canadian wildfires that are behind most of these alerts are just too widespread and too remote,” said Matt Taraldsen, supervisory meteorologist for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. “Those fires are going to keep going until the snow puts them out.”

Generally, air quality has improved in Minnesota over recent decades. By 2017, total emissions from all sources in the state had decreased significantly while overall trends in the air quality index showed far more good days and almost no days requiring warnings to stay inside. Much of that improvement came from more stringent air quality rules targeting tailpipe emissions and power generation at both the federal and state levels.

That positive trend in air quality started to change within the last several years, however, when wildfires both in and out of the state created harmful smoke plumes that drifted over Minnesota, triggering increasing numbers of air quality index (AQI) alerts.

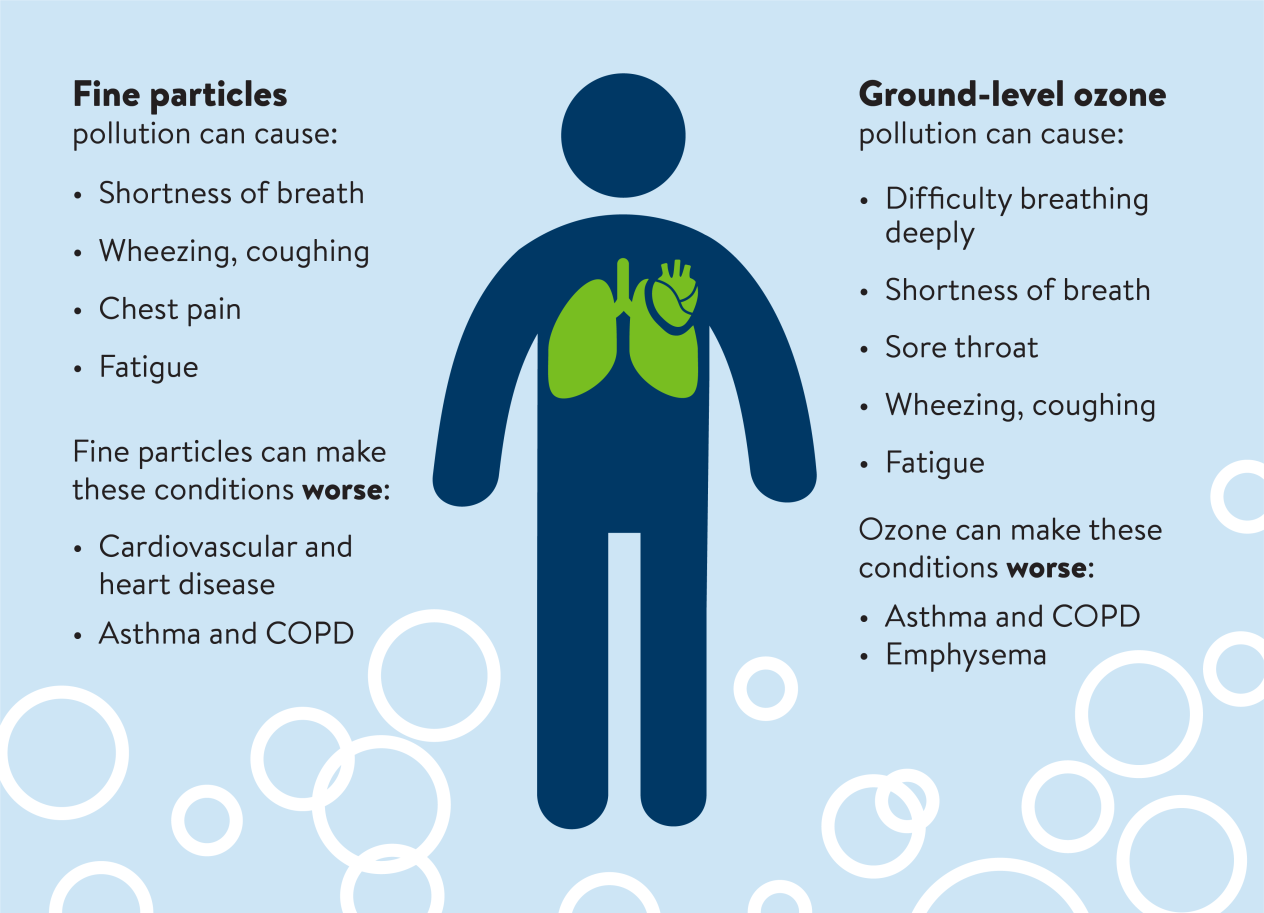

In use in Minnesota since 2000, the AQI factors in daily measurements of four pollutants in the air that can harm human health: carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). AQIs can range from 0 to 500 and are assigned a color code depending on how much of a risk they pose for human health. An AQI below 50 (green) is generally considered safe for everybody; an AQI above 100 (orange) is considered harmful for some people; and an AQI above 150 (red) poses health problems for everybody. The MPCA issues AQI alerts when its staff of meteorologists anticipate AQIs of 100 or above.

In the winter, air quality tends to suffer when stagnant weather causes PM2.5 emitted from local sources of pollution — usually cars or heating sources — to build up close to the ground. That PM2.5 is so small, it can easily enter the bloodstream when inhaled, damaging the lungs and heart. Short-term exposure can aggravate lung disease and trigger asthma attacks. Long-term exposure increases the chances of developing a number of health problems, including cardiovascular disease and lung cancer. According to Taraldsen, Minnesota typically has just one “stagnation event” every winter because the state’s background levels of pollution aren’t bad.

Ozone will typically trigger one or two air quality alerts per year during the summer when ultraviolet radiation from the sun reacts with volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the air. Wildfires within the state will also release PM2.5 and cause summer air quality alerts.

However, the record number of AQI alerts this summer came from the plumes of smoke from Canadian wildfires that drifted south. That smoke contained not just massive amounts of PM2.5 but also more VOC than expected, leading to more ozone-triggered AQI alerts (five) and more alerts over more days than ever before.

By the middle of September, the MPCA had issued a total of 20 alerts covering 52 days, eclipsing the previous record of 13 alerts covering 42 days in all of 2021. (The final tally for 2023 came to 22 total alerts covering 52 days.) The state might have seen a red AQI day once every decade previously, but in 2023 alone, the MPCA has issued 14 red alerts, which Taraldsen says is highly unusual.

(According to Taraldsen, this year the MPCA has yet to issue a purple alert — for an AQI above 200 — as it did in 2021. Nor has the MPCA issued any alerts for smoke from wildfires within the state.)

While wildfires tore through Canada last year too, Taraldsen says that Minnesota’s air quality didn’t suffer in 2022 the way it has in 2023 due to weather patterns.

“Even if you have a lot of fires, the weather dictates where that smoke will go,” he says. “How much of that smoke gets to us really depends on the jet stream, and the polar jet stream has been pushed up far north by El Niño.”

One large reason the MPCA employs meteorologists like Taraldsen and his staff is so they can figure out where those weather patterns take the wildfire smoke and to forecast not only whether that smoke and the PM2.5 will settle along the ground rather than remain aloft in the atmosphere but also whether the smoke will arrive in concentrations enough to warrant an AQI alert.

Compounding all of this is climate change, according to Alissa Reynolds, a wildfire specialist with the Division of Forestry at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

“We’re seeing more extreme weather events, more droughts occurring, and that contributes to fuel loading in the forests,” Reynolds says. “It’s also led to a longer fire season, an extension of about a month or so. Right now, it’s an almost exponential acceleration of the drier period.”

That means wildfires not only have more time to burn larger swathes of forest, they also burn hotter, lofting more smoke higher into the atmosphere to travel farther than before. And the large number of trees damaged by this year’s wildfires pose a substantial risk for fueling even more wildfires in subsequent years.

Reynolds is not alone in her assessment. A study that the World Weather Attribution Group at London’s Imperial College issued last month determined that climate change “more than doubled” the chances for extreme wildfires in Eastern Canada this year and that the likelihood and intensity of such fires are projected to continue increasing in the future.

As if that weren’t enough, Taraldsen says that climate change will likely cause an extension of the ozone season as well, leading to even more AQI alerts. And both Taraldsen and Reynolds noted that Minnesota is currently entering its fall wildfire season, in which fallen leaves, summer-dried trees, and lower humidity — not to mention the state’s ongoing drought — combine to create larger wildfires that are more challenging to put out.

In the meantime, the Canadian wildfires will continue to burn, and Taraldsen says his team is watching the jet stream to see if it will drop back down over Minnesota and bring with it more Canadian wildfire smoke.

“We will see more bad air quality days in 2023, we’re just unsure how many,” he says.

While the record number of AQI alerts doesn’t necessarily land as good news, Reynolds said that as they become more prevalent, people become more aware of the risk of wildfires, particularly here in Minnesota.

“We haven’t had as many wildfires in Minnesota as expected, considering that we’ve had similar conditions to 2021, when we had a lot,” she says. “Given that 98% of wildfires in Minnesota are human caused, I’d say that increased awareness around wildfires from the AQI alerts is helping our cause.”

Beyond sharpening his team’s skills in accurately forecasting a bad AQI day, Taraldsen says the record number of alerts has also led to a change in how people factor air quality into their daily lives.

“People tell us they didn’t really consider it before — they didn’t even know we did air quality alerts before 2021 — but now they check the air quality when they go out the door the same way they check the forecast for rain,” he says. “We have gotten feedback that we’re issuing too many alerts, but then we hear from somebody whose kid has asthma, and they tell us they really appreciate the work we do.”