MPCA adds three bodies of water to impaired waters list for PFAS contamination in fish

The amounts of PFAS chemicals that MPCA researchers find in lakes, rivers, and streams across Minnesota are almost too miniscule to comprehend — measured in parts per billion or even parts per trillion. At the same time, those amounts can be far too great for the fish and wildlife in and around those bodies of water.

But determining how much PFAS is too much PFAS differs depending on how — and in some cases where — it’s measured, which adds a layer of complexity to the MPCA’s determinations about which lakes, rivers, and streams it has added to its biennial impaired waters list for PFAS contamination.

Fish as indicators

Of the 199 impairments over 54 bodies of water that the MPCA has proposed adding to the state’s impaired waters list for 2024, three — Crystal Lake in Robbinsdale and Sargent Creek and Miller Creek in Duluth — are due to high levels of PFAS, the per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances commonly known as “forever chemicals” that have been linked to elevated risks of health problems in people.

Their additions bring the total number of Minnesota lakes, rivers, and streams considered impaired for PFAS pollution to 26. Impairment, however, can mean different things in different bodies of water. Some may be unsafe to swim in due to bacteria. Some may see algae blooms from high nutrient levels.

For those lakes, rivers, and streams that the MPCA considers impaired for PFAS contamination, it all depends on whether the fish caught in those waters have absorbed too much PFAS.

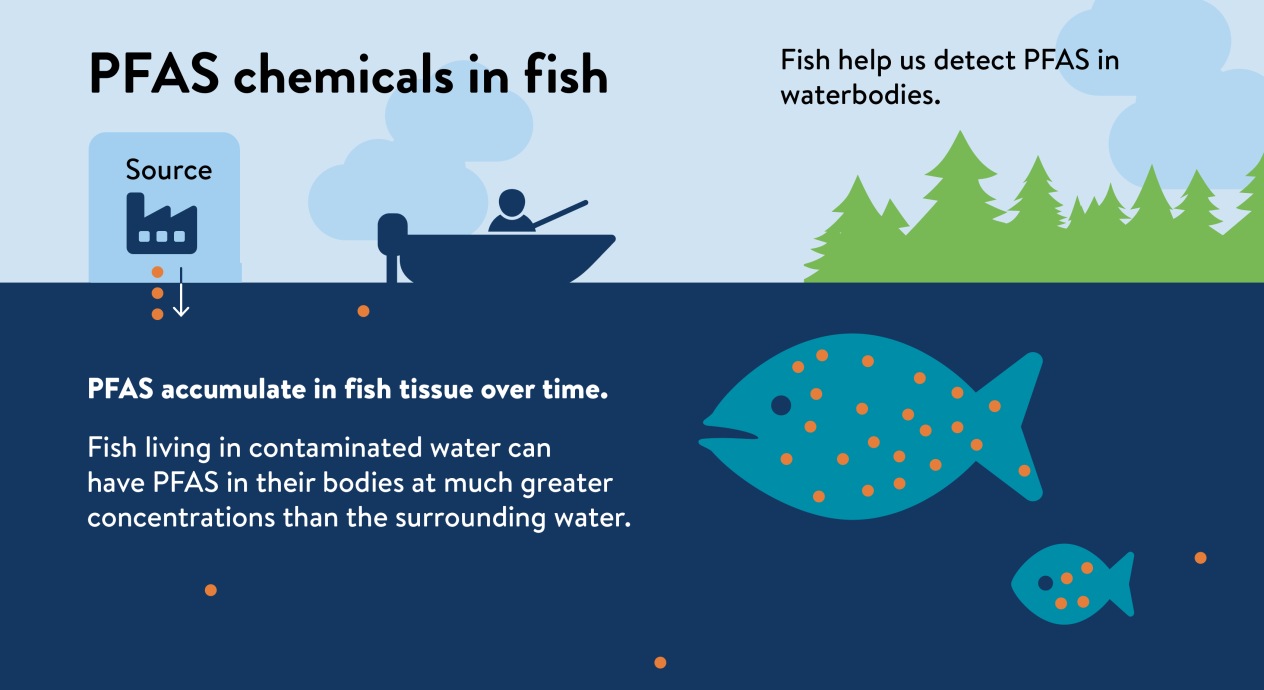

Fish in PFAS-polluted waters act as bioaccumulators, which means that PFAS chemicals build up in their bodies to much higher levels than the surrounding water, which can shuttle PFAS chemicals along relatively quickly. As a result, fish become far better indicators of the presence of PFAS in a body of water than the water itself.

This makes for a useful tool for MPCA scientists like Summer Streets, who studies PFAS levels in fish across the state.

“The water concentrations that result in these high fish concentrations don’t have to be very high,” Streets says. During one test, for example, water concentrations of PFAS at Sargent Creek came in at 36 parts per trillion while PFAS concentrations in fish taken from the creek came in at more than 500 parts per billion, or more than 13,000 times as much.

PFAS and firefighting foam

Sources for such high concentrations of PFAS might be an industrial facility releasing contaminated water into a waterway, an old landfill, or, as is likely the case for Miller and Sargent creeks, firefighting foam.

An MPCA investigation into the elevated levels at Sargent Creek determined that the PFAS in the creek came from aqueous film forming foams (AFFF) used at Lake Superior College’s Emergency Response Training Center outside of Duluth, where firefighters in training once practiced with the foams.

Miller Creek, which runs past the Minnesota National Guard’s 148th Fighter Wing base at the Duluth International Airport, joins two other St. Louis County bodies of water — Fish Lake and Wild Rice Lake — that are already on the impaired waters list due to PFAS chemicals linked to firefighting foam used at the base.

AFFF is one of multiple firefighting foams used to put out Class B fires, or those fueled by flammable liquids. The PFAS chemicals in AFFF make the foam particularly effective against jet fuel fires, but they have also grabbed the attention of plenty of regulators and legislators around the world. Here in Minnesota, the state has prohibited the use of AFFF for testing or training purposes since July 2020, and earlier this year Governor Tim Walz signed legislation prohibiting all use of firefighting foams containing PFAS with limited exceptions starting in January 2024.

Those exceptions are for petroleum refineries and terminals as well as airports, which can continue to use PFAS-containing foams in Minnesota until the state’s fire marshal determines a fluorine-free firefighting foam (F3) is commercially available in sufficient quantities. The Department of Defense has so far approved one F3 for use at land-based airports, which the Federal Aviation Administration also considers appropriate for airport use.

According to a statement from the 148th Fighter Wing’s Commander, Col. Nate Aysta, the wing discontinued the use of AFFF in training exercises or for testing equipment but continues to use it for emergencies.

“The safety and health of our airmen, their families and our community partners are our priority,” Aysta says. “We live, work, and attend school in the community we serve. We share the concerns about PFAS and have been working with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency since 2007, when it was brought to our attention that PFAS contamination may have negative impacts on groundwater. The Air Force and the National Guard are committed to being proactive in its efforts to address PFAS-related issues and maintaining an open dialogue with our community members and stakeholders.”

David Kline, the vice president of advancement and external relations at Lake Superior College, says that the Emergency Response Training Center no longer uses foams of any kind in its training and that the area around the training area is now lined with plastic as an interim measure to collect and treat water coming off that paved surface from ongoing firefighting exercises.

“There’s still PFAS in the soil, so we’re making sure that we’re not pushing that runoff into Sargent Creek,” he says. “The bottom line is that we have to keep training firefighters, but we also have to stay in compliance.”

Differing thresholds

Firefighting foams containing PFAS might be on their way out now, but their repeated use for decades — as opposed to one-off emergency uses — has led to excessive levels of PFAS in the environment.

“The training sites got foam repeatedly, and so there’s a buildup of PFAS,” Streets says.

Enough not just to produce detectable levels of PFAS in fish but also to surpass the larger of two thresholds in Minnesota for adding a body of water to the impaired waters list due to PFAS. According to Streets, certain waters in the Twin Cities metro area have site-specific criteria of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) concentrations in fish of just 0.37 parts per billion to be added to the list.

“That’s essentially the detection limit,” she says. “It’s very restrictive.”

For waters in the rest of the state, however, PFOS concentrations in fish have to rise above 50 parts per billion for the MPCA to add them to the list. Streets said there is some interest in standardizing PFAS criteria across the state, but those discussions are ongoing as the MPCA establishes statewide water quality standards for PFAS set to take effect in 2026.

In the meantime, the MPCA has expanded the list of PFAS chemicals for which it considers a body of water impaired for some specific sites in the metro area. Through 2020, that list consisted of just PFOS detected in fish tissue. Since 2022, it has included perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS), perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), and perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS) found in the water itself. Actual assessments for impairment using those additional PFAS chemicals will start in the coming years.

Exactly how long Miller Creek, Sargent Creek, and the two dozen other waters in Minnesota considered impaired for PFAS chemicals will remain on the impaired waters list remains to be seen. As Leya Charles, a research scientist with the MPCA, notes, removing sites from the list can take years, if not decades, depending on the pollutant found in it.

“It only takes a little bit of data to show it’s impaired, but a lot to show it’s improved,” she says.

But if there’s any bright side to the issue of PFAS in waters, Streets says, it’s that PFAS chemicals can move quickly through flowing waters.

“PFAS are very mobile,” she says. “They will move on to the next water, and over time will dilute as they move through the system. And with decreased water concentrations you will see a relatively rapid decline of PFAS concentrations in fish.”

That means one relatively straightforward action can drastically reduce the amount of PFAS in a relatively short amount of time, Streets says.

“Number one: cut off the source,” she says. “If we do our best to get really active about stopping the sources, we’re actually going to have a real impact in our timescale that is noticeable to us.”