The MPCA will distribute $4.85 million to build more networks of community air sensors in the Twin Cities metro area

It’s easy to miss the network of air quality sensors that Minneapolis has deployed throughout the city. Some sit atop lampposts or beside red-light cameras, blending into the background of urban infrastructure. Others are entirely out of sight from public view in backyards and along alleys in residential neighborhoods.

Individually, the data they generate provides crucial information for anybody with asthma or who wants to know whether the air is clean enough for a run in the park. Collectively, however, the sensors make it possible to collect data on air pollution hotspots, analyze traffic patterns, and even inform policy decisions to improve air quality throughout the city.

“There is power for residents to have this information,” says Jenni Lansing, the senior environmental project manager for the Minneapolis Health Department and the coordinator of the city’s air monitoring network.

That power is the reason the MPCA is now offering $4.85 million in grants to create more community air sensor networks throughout the Twin Cities metro area.

Tighter networks lead to better data

While this might be the first time that the MPCA has funded networks of air sensors for communities, it’s not the first time that the agency has studied community-wide networks and how to get useable data out of them.

From 2019 to 2021, the MPCA used $500,000 in funds from the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources to build and run a pilot air sensor network in the metro area. That network distributed 50 pod sensors from AQMesh across 44 ZIP codes and tracked several air pollutants, including sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide, ozone, and particulate emissions.

While the sensors are not regulatory monitors and thus don’t provide data that could be used in an enforcement case against a polluter, “that doesn’t mean we can’t use that data for screening or forecasting,” according to Megan Kuhl-Stennes, an air policy planner for the MPCA. “Overall, these sensors can give us a sense of what might possibly be going on, and they might show us where we need to put additional regulatory monitors.”

Yet, as Kuhl-Stennes and others at the MPCA discovered with the study, it was difficult to get conclusive data from such a widespread network.

“One sensor in each ZIP code was not a small enough area to gauge differences in air quality from neighborhood to neighborhood,” she says.

Fortunately, not long after that project wound down, the city of Minneapolis won a separate grant to launch its community air monitoring project, one that could get more granular data on the neighborhood scale.

According to Lansing, Minneapolis set up the network in response to concerns from its residents.

“Community members were often frustrated to hear that air quality is generally good in our area when they were experiencing local events that indicated poor air quality,” she says. “This led to increased discussions of focusing on and testing hyper-local air quality and the desire for more information.”

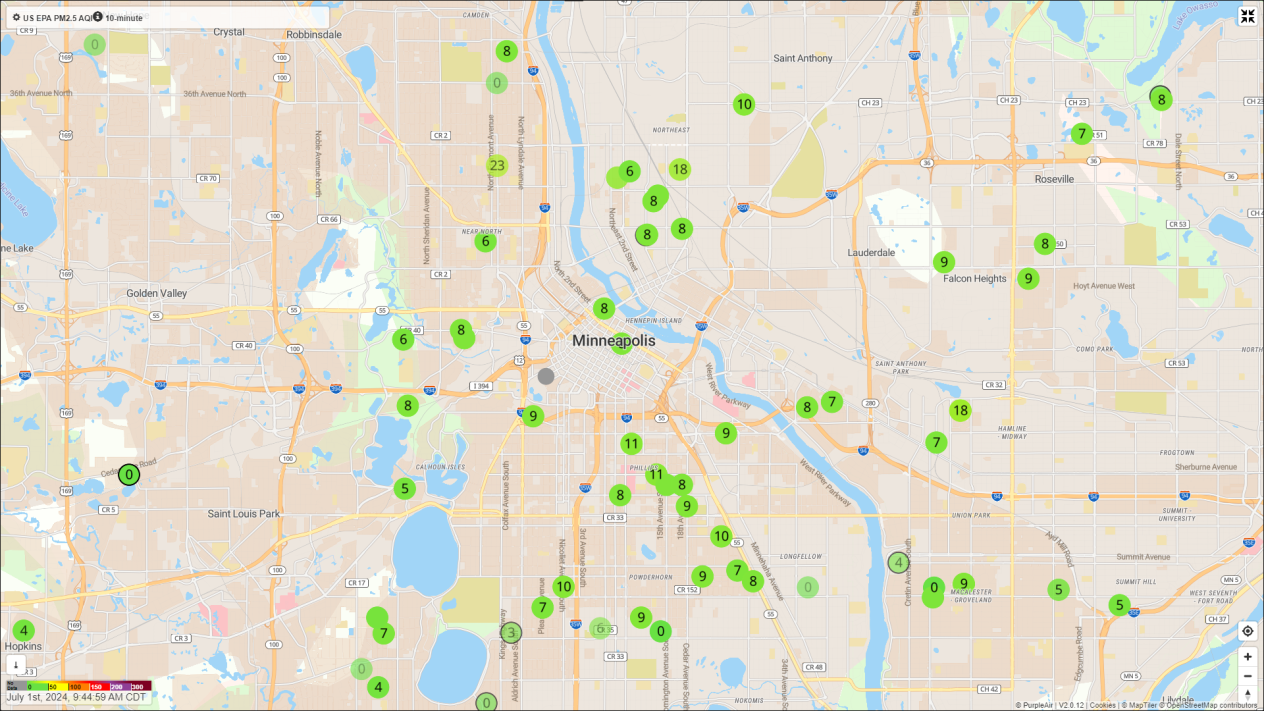

To build out the network, Minneapolis borrowed 30 of the AQMesh sensors from the MPCA’s pilot network for placement on city-owned light poles, then added 80 PurpleAir sensors that it distributed to residents willing to host one. The PurpleAir sensors started to go up in the summer of 2022, with the AQMesh sensors following in July 2023. More sensors of different types are expected to follow this summer.

While the AQMesh sensors can track multiple air pollutants like carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone, and total volatile organic compounds, the PurpleAir sensors only track particulate matter. On the other hand, the PurpleAir sensors can provide real-time data, while the AQMesh sensors cannot. That makes a significant difference in how Minneapolis residents experience air pollution in their own backyards.

Air pollution from a variety of sources

Lansing, who has a PurpleAir and a TSI BlueSky sensor mounted to a gazebo in her backyard, recently ran a little experiment. While visiting with neighbors around their smokeless fire pit, she wondered whether the PurpleAir sensor would register the emissions from the fire from two backyards away. She opened the PurpleAir map on her phone “and yeah, it picked it up.”

She says residents have noticed spikes or above-average readings from many different localized sources of air pollution, including backyard fires, grilling, gas-powered lawnmowers, and highways. “We have sensor hosts who check their sensor daily and report to us how they use the data.”

Kuhl-Stennes said it’s easy to tell when different communities shoot off their Fourth of July fireworks by watching the map. “You can see it spread across the city,” she says.

Then when particulate-filled wildfire smoke descended on the state in May, she used her sensor to determine when it had cleared off enough to open her windows again.

Anecdotally, according to Lansing, residents have expressed surprise that the real-time map shows better air quality than they expected.

But the greater value of the data, Lansing says, is how the City, businesses, and residents can put it to use to influence behavioral changes. Poorer air quality around certain types of businesses, for instance, could lead to regulations that curb air pollution from those businesses or to funding opportunities for businesses to adopt greener practices. Similarly, Minneapolis could use data from the network to educate residents about the benefits of switching to electric lawn equipment.

Putting sensor data to work in new ways

One innovative project made use of the data that the City gathers from its sensors to directly warn Minneapolis residents of poor air quality.

In the summer of 2023, Rob Hendrickson, a programmer and Minneapolis resident, worked with Lansing’s office to develop what he calls the SpikeAlerts system, an open-source text message service that reads through the data from Minneapolis’s sensors then notifies residents if air pollution in their vicinity reaches unhealthy levels.

“It started with the wildfire smoke and all the air quality alerts last summer, which led us to think more about how to access information on local air quality,” he says.

While similar text alert systems exist in places like Detroit and Southern California and the PurpleAir sensor data is available on the company’s website, the SpikeAlerts system differs in that it can send out alerts on a block-by-block basis. It also reaches out directly to residents who sign up for alerts.

“This is really about the community being in control of this information, that’s the most important thing,” Hendrickson says. “Otherwise, who is the sensing really for?”

Legislature funds more sensor networks

To establish more sensor networks like the one in Minneapolis and to create more data to inform decisions that reduce air pollution, the MPCA’s pilot community air monitoring grant program will use funds that the Legislature set aside in 2023 to help nonprofits in the metro area deploy the networks, collect the sensor data, and communicate that information to residents. The networks can use any type of sensor, including mobile sensors. Projects that implement networks in environmental justice areas, near facilities with recent air permit enforcement actions, and in areas with high illness rates linked to air pollution will get priority consideration for the grant.

“Sensors can really be a tool to address the disproportionate impact of air pollution,” Kuhl-Stennes says. “In these projects we’re talking about, we ask that the communities share the data with the MPCA, but the community owns that data and can manage it for their own benefit.”

So even though the sensors may remain hard to spot even with new networks funded by this grant program, the data that the sensors generate and the improved air quality that will result should be hard to miss.

The MPCA will accept applications for the grant program through July 26.