Less lake ice has implications for recreation, the environment, and fish and wildlife

We might have had another sufficiently cold winter in Minnesota to support some ice fishing and pond hockey — certainly a colder winter than the one before — but climate experts point out that winters in Minnesota are still warming at a rapid and accelerating pace. That carries big implications not just for Minnesotans’ winter pastimes but also for their health, the environment, and for the state’s economy.

Many of those implications can be seen in the ice that covers Minnesota’s 10,000 lakes every winter.

130 years of data

As a climate change research scientist with the MPCA, Carl Stenoien analyzes data on how long Minnesota lakes stay frozen. That dataset now goes back to 1895 when somebody recorded 137 days of ice duration on Lake Sagatagan.

“Some of the data came from when people kept records on local lake ice conditions inside their kitchen cabinets,” he said. Whether it was practical for them to do so or they just noted the conditions out of curiosity, those records provide valuable context.

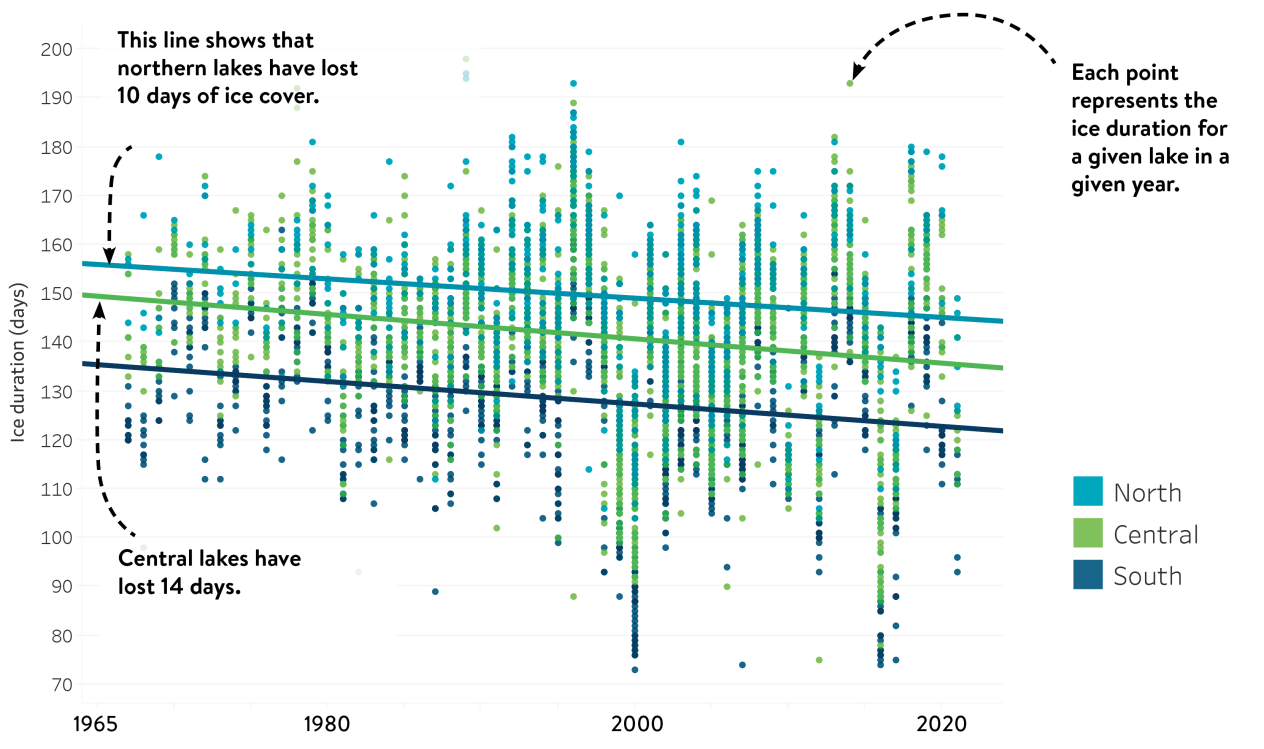

More historical data from more lakes goes into that dataset all the time, though now with the purpose of documenting the effects of climate change. Clear trends attributable to climate change start showing up around 1970, Stenoien said, when a gradual loss of lake ice ramped up to the current rate of about 2.5 days per decade.

“It’s always important to recognize annual variations, but what we’re seeing now are long-term trends backed by the data,” Stenoien said.

Overall, lake ice duration across Minnesota has decreased by up to 17 days over the last 50 years. Over the last 100 years, it’s as much as 27 days.

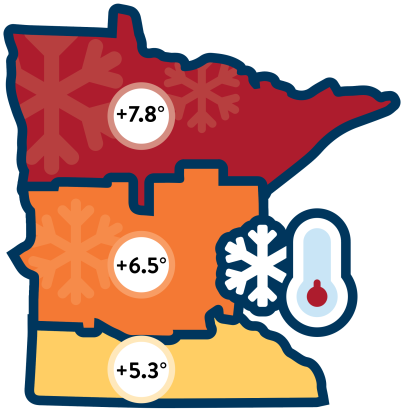

As Kenny Blumenfeld and Peter Boulay, climatologists for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, pointed out, air temperature is a more direct measurement of how quickly the state is warming than ice coverage, but it tells a similar story: Since 1895, winter low temperatures have increased from around 5 to nearly 8 degrees Fahrenheit, faster than the roughly 3-degree average annual temperature increase. Minnesota’s also seeing far fewer bitterly cold temperatures; readings of 35 below in the north and 25 below in the south have dropped by 70% to 90%.

“It just doesn’t get as cold as it used to,” Blumenfeld said.

As Stenoien put it, our winters “are softening around the edges.”

While Blumenfeld said these trends don’t mean that one winter will be warmer than the last or that lake ice will consistently drop year over year, “the trends are measurable and significant across the state and it’s likely that winter will continue being our fastest-warming season, meaning further reductions in lake ice cover in the years ahead.”

A number of factors contribute to these trends, but he said the main reason for them is the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the air.

Effects on fish and wildlife

What’s a few extra degrees or a few less days of ice cover mean, then?

To begin with, the less ice cover on lakes, the more time the water in those lakes warms. As a result, lake temperatures are also on the rise, especially in months like November and March when lakes used to have far more ice.

Warming lake temperatures have already impacted Minnesota’s native fish species. Cisco, a species that other fish and loons eat, live in cold and deep waters, but face increasing habitat loss as lakes warm. Walleye are more adaptable, but as the DNR notes, rapidly warming water can disrupt walleye spawning and cause their eggs to hatch prematurely. Both have disappeared from Minnesota lakes where they were once abundant, replaced with species like bass that can tolerate warmer lakes.

For some lakes, entire food chains depend on ice coverage. As a recent research review in the journal Science noted, clear ice allows light to reach the water beneath and fuel the growth of algae, which provides a food source for zooplankton grazers and the larger animals that feed on them.

More fish isn’t always better, either. Smaller lakes may actually need longer ice coverage to kill off fish populations in the winter. When that doesn’t happen, the fish can overpopulate and lake conditions may no longer support existing communities of bugs and amphibians or be as attractive to migrating ducks.

Effects on the environment

As a natural process, ice cover benefits lake health too. With less ice cover, waves erode more coastline and add more sediment to lakes, methane production from natural decay in lakes goes up, and carbon storage in lakes goes down.

Ice coverage also keeps a lake’s water from evaporating. This not only prevents lake-effect snow, it also prevents excess moisture from rising to the atmosphere and contributing to more devastating storms throughout the year.

Invasive aquatic plants like curly leaf pondweed and Eurasian watermilfoil also stand to benefit from less ice and longer growing seasons.

Effects on human health and culture

There’s a human aspect to warming winters too. Part of that is the impact to human health and safety. Warmer lake water leads to more toxic blue-green algae blooms that can sicken people in the summer. More directly, thinner ice presents more danger for falling through when trying to cross it.

Another human aspect to warming winters and less ice coverage, as the authors of the aforementioned review in Science noted, is the loss of cultural identity and traditions for people who live near lakes that ice over. Ice means jobs that contribute to the economy, afternoons ice skating with your friends and family, and ice fishing tournaments that contribute to a sense of community.

"I love skiing and ice fishing," Stenoien said, "but it’s getting harder to do these things without consistent ice and snow."

What are we doing about it?

While climate change is a global problem, here in Minnesota we have developed a Climate Action Framework to address and prepare for the effects of climate change.

Part of that framework calls for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Minnesota by introducing clean transportation alternatives, making homes and buildings more energy efficient, and switching to carbon-free energy sources.

The framework also calls for building resilience among Minnesota’s communities for the effects of climate change. The sooner they plan for it, the better Minnesotans will be able to adapt to the loss of lake ice and other effects of climate change.